Gracious Reader,

In light of the unconscionable antisemitic attacks at Brown University and in Australia this past week, our work to promote respect for human dignity feels more urgent than ever. In response, I am working as hard as I can to finish the children’s book so we can begin teaching these ideas in schools and in our homes. The aim is to help future generations recognize the profound gift of being human, in themselves and in others. That recognition is the moral and intellectual foundation of civility.

I’m delighted to share an update on the children’s version of The Soul of Civility, and to share its introduction with you. My hope is that this book will serve as a meaningful resource that enriches learning communities of every kind. If you’d like to use this work in your school, community, or homeschool co-op, please feel free to contact me.

I also very much welcome your feedback. If you’d like to read early chapters and share them with your little ones or in your classroom or homeschool setting, I would be grateful to hear your reflections and experiences as the book continues to take shape.

Warmly,

Lexi

Heroes and Villains

Dear Parents and Teachers, Mentors, and Friends,

This book was born from a simple but profound belief: the purpose of education is not merely to fill minds or meet market needs, but to form souls and to cultivate whole human beings. This idea may appear novel, but it is in fact ancient.

Our word “education” comes from the Latin educare, meaning to lead forth or bring out. True education was always understood as drawing forth what is most noble and best in us and relegating what is disordered to its proper place. Our word “school” comes from the Greek schole, meaning leisure, unstructured and spacious time for reflection, self cultivation, and joy. My hope is that this book helps parents, teachers, and students recover this ancient vision of learning as restful self cultivation. The pressures of modern classrooms and modern life, test scores, rankings, literacy statistics, college admissions metrics, often remove joy from learning for teachers, parents, and students alike. I hope this work helps restore joy, wonder, and rest.

True education shapes what we know (orthodoxy), what we do (orthopraxy), and what we love (orthopathos). It forms the whole person, heart, head, and hands, in harmony. In Greek, these ideas are captured in the words orthodoxy, orthopraxy, and orthopathos.

In cultivating our minds, it helps us think well. This is orthodoxy, from the Greek words orthos, meaning correct, and doxa, meaning belief. In cultivating our actions, it helps us act well. This is orthopraxy, from the Greek orthos and praxis, meaning practice. And in cultivating our hearts, it forms our loves. This is orthopathos, from the Greek orthos and pathos, meaning feeling or affection.

The goal of this pedagogical triad, orthodoxy, orthopraxy, and orthopathos, is to cultivate our humanity to its fullest, bringing forth what is most noble and best in us and relegating the ignoble within us to its proper place.

This is how future citizens and leaders across history have been formed: shaped by stories that cultivate, inspire, and challenge, then deployed in service of making the world a better place. This forgotten vision of education prepares us to serve others and to live well together in the shared project of self governance that is a democracy.

Across time and place, stories have been the central tool in this project of cultivation and formation of young persons. The stories in Heroes and Villains come from the oldest wellsprings of human wisdom. They remind us that the great questions of life, how to live well with others, how to be just and kind, how to use power wisely, are not new. Gilgamesh, Ptahhotep, Aesop, and others wrestled with the same questions we do today.

Each story invites children, and the adults who love them, into the Great Conversation about the foundational questions of life, questions of origin, purpose, and destiny, such as: Who am I? What does it mean to be human? What is the best way to live? What is my purpose in life?

These questions are foundational to civility because they are foundational to the human social project. Thoughtful people across time and place have reflected on them, and every student, every person, ought to have the opportunity to ask, and to answer for themselves, these questions as well.

Exploring how others before us have answered them through their own lives invites us to do the same. Reading together shapes our perception of the good, helping us recognize it, admire it, and desire to live in alignment with it. It also helps us see the bad clearly so that we can name it and turn away from it.

As parents and teachers, mentors and friends, you are partners in this sacred task of cultivating young minds, bringing out the best in them, helping them know themselves and find their place in the world. When stories are read at home and echoed at school, their lessons take root in daily life. The stories give children a shared language, and we, the people they love and look up to, must embody that language through our example. Together, the words and stories they hear and the lives they watch form a moral vocabulary and a common memory.

I wrote The Soul of Civility: Timeless Principles to Heal Society and Ourselves with my own children in mind, hoping it might help create a gentler world for them to grow up in, a world where their dignity and personhood are honored and where they learn to honor others as well. I also know that I am their first, best, and most important teacher. I am grateful for the many unseen helping hands who share this work with me, the teachers, friends, and family whose care shapes my children in ways large and small. Raising children happens within an ecosystem, which is why I have addressed my book to all the influences in a young student’s life, not to teachers or parents alone. It is a partnership. We need one another, and they need each of us.

Creating The Soul of Civility for my children was not enough. I yearned for them to know its ideas, to embody them, as well. At the time of this writing, my three children, all five and under, traveled with me to one hundred and thirty five cities and five countries as I shared this work. They knew the title of my book, but not the lives of the heroes that inhabited its pages, and I wanted to change that. I began telling them stories at night about the heroes and the villains of civility, recording myself as they drifted to sleep, then transcribing those stories after they closed their eyes. They loved each of these and asked for them again and again, never tiring of these heroes and villains of civility.

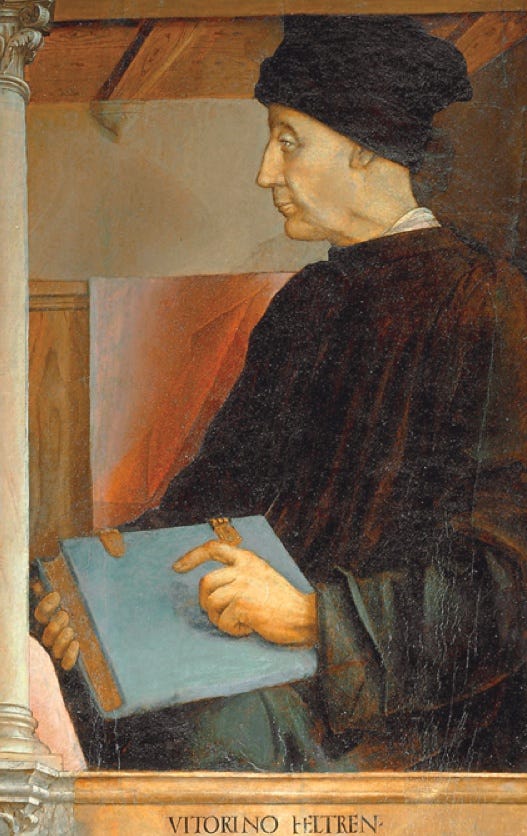

These stories draw on the traditions of three of history’s greatest storytellers, Aesop, Christ, and Plutarch. Aesop’s fables used talking animals and simple plots that we all know, such as the tortoise and the hare, the goose that laid the golden egg, or the boy who cried wolf. In the ancient world they were central to early education. Children copied and memorized them to learn reading and writing, and also drew from them as a tool in a toolbox: each held lessons about how to cultivate practical wisdom, or prudence, understood as choosing the correct action for a specific situation. Christ’s parables are also brief, but they are rich and layered. They are simple enough for small children to enjoy, using familiar images such as seeds or lamps that are accessible to all on first hearing. Yet they are powerful and compact. Communities have studied, taught, and revisited them for millennia because a new insight emerges each time. Plutarch, the ancient Greco- Roman historian, used biography for instruction. He was a careful scholar who cared about telling the stories of those who came before us in order to help readers live better in the present. He examined lived character rather than abstract description. Although he was a Greek writing under Roman rule, he did not adopt a nationalistic lens. In his paired biographies of famous Greeks and Romans, wherever he saw admirable conduct he praised it, and wherever he saw vicious conduct he condemned it. In the opening of the Life of Alexander the Great, for example, he wrote that he was looking for “signs of the soul” in action. Plutarch’s Lives is a sustained study of character in motion, and my hope is that this book is as well.

Together, these traditions show how short, clear stories, whether fable, parable, or biography, or a blend of all three, can inspire and instruct readers of any age or background. My aim is for this book to be read in homes and K to 12 classrooms, nourishing the hearts and minds of students of every age, along with the adult who reads it with them. Each story has general discussion questions, and each question has a “Civility insight,” or an explanation of how it will help students understand and apply these ideas to their lives. I also offer expanded age appropriate discussion questions at the end. I also include at the end of each story a correlated reference to my book, The Soul of Civility, for people who want to dig deeper into these themes on their own, before or after bedtime or class.

At the end of each chapter, you will also find suggested activities organized according to orthodoxy, orthopraxy, and orthopathos, meant to help parents and teachers nurture head, hands, and heart together.

Orthodoxy activities are designed to help students grasp the story and its themes. They take the form of traditional discussion questions, offered as a general set, with expanded questions by age band.

Orthopraxy activities invite students to practice what they have learned through simple, joyful exercises such as letter writing, role playing, reenacting scenes like Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s battle and reconciliation, and creating artwork or coloring inspired by the story. Optional enhancements are included to help students learn about and appreciate the civilizational contexts of these heroes. For example, students can build a tablet out of clay and mark it with cuneiform, just as the ancient Sumerian scribes who wrote down the Epic of Gilgamesh once did. Or they can make paper in the style of ancient Egypt from “papyrus” reeds, then write a letter or create their own maxim as Ptahhotep did, and as Egyptian scribes practiced for centuries.

Orthopathos activities cultivate right affection, the ordered love that makes us capable of caring for humanity. They help students learn to see the world with generosity, to feel curiosity about others, and to develop a stable concern for the people around them. Across history, educators understood that moral growth begins when we step outside ourselves and imagine the experiences of others, allowing their joys and sorrows to matter to us. As Shelley suggested, the work of becoming a good person involves enlarging the inner life so that we can identify with what is beautiful in thought, action, or another person. Orthopathos supports this enlargement by training students to order their loves toward what is true, good, and beautiful. These activities include guided imagination exercises, empathy practices, gratitude reflections, and encounters with moments of beauty, wonder, and the sublime, meant to humble us and instill a sense of awe. They help students feel the meaning of the story and recognize the dignity of others. They are meant to inspire parents and teachers to create additional practices that cultivate the heart, just as orthodoxy cultivates the mind and orthopraxy cultivates action.

You will also find a brief “Did You Know” section with each story, offering background notes about the time period, culture, or historical figure. These can deepen an adult’s understanding or be read aloud in the classroom to enrich the lesson.

Too often today, in classrooms, in homes, and in life, we are satisfied when children do and say the correct thing. That is orthopraxy, right practice. It matters. Orthopraxy is politeness. It is technique, etiquette, and manners. But outward action alone is not enough. There is also orthodoxy and orthopathos, which is where civility enters. Civility is an inner disposition of the heart. It begins with seeing others as our moral equals, human beings with inherent dignity and worth. Civility is the art of human flourishing. It is seeing and treating others as valuable and equal, no matter who they are or what they can do for you. It is respecting people just because they are people, human beings just like us. Orthodoxy is this right understanding, the clear recognition that every person is a miracle. This is one of our central tasks as parents and teachers, mentors and friends: helping children see the profound gift of being human, in themselves and in others. But even orthopraxy and orthodoxy together are incomplete. We are not only mind and body. We are also heart, and the heart is what sustains right thinking and right action when they are difficult. This is orthopathos, right feeling. It is not only knowing that others possess inherent dignity, but also cultivating the affection that aligns with that truth. This is where stories are helpful to cultivate orthopathos. It is possible to hold the right ideas, and to do all the right things, while carrying a heart that is out of alignment. That love takes work. Civility requires hands, head, and heart. It calls for right action, right understanding, and right motivation, so that we act well for the right reasons.

I hope this book becomes a resource that parents and teachers can make their own. Each story is a starting point rather than a fixed script. Treat it as a canvas. Build activities around it. Ask new questions. Connect it with the other subjects you are teaching. That is where the joy of learning comes from, the moment when ideas from different places begin to illuminate one another.

Use the story of Gilgamesh, the oldest story in the world, when you explore ancient Sumer and Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization. Let your unit on ancient Egypt grow from the wisdom of Ptahhotep, author of the oldest book in the world. Bring the truth telling courage of Edward Coles into a social studies or civics discussion about slavery and the founding era. Pair the story of Hannah Arendt with your study of World War II and the Holocaust. Let each narrative become a thread that links history, literature, ethics, geography, and the questions your students are already asking.

My hope is that these stories spark creativity in both home and classroom, opening space for crafts, projects, cross subject exploration, and conversations that grow well beyond these pages.

Education becomes formation when what we learn shapes what we love, and what we love shapes who we become. With children, the messenger becomes part of the message, so learning with someone they love has its own formative power. My hope is that these stories make room for love, joy, and trust to grow. May these stories awaken wonder, nurture wisdom, and help us, all ages together, grow in civility, curiosity, and joy. And as we share these stories, may we allow the stories to call forth the best in us, too, and to live in a way that gives those who watch us something worthy to follow.

With gratitude and hope,

Lexi

In the News

PBS: Author Alexandra Hudson explores the difference between politeness and civility: Steve Adubato welcomes Alexandra Hudson, author of “The Soul of Civility: Timeless Principles to Heal Society and Ourselves,” to explore the difference between politeness and civility, and how embracing human dignity can bridge the divide in times of political tension.

Indy Politics: Holiday Survival 101: How To Deal With “That One Relative”: The holidays are here, which means two things: calories don’t count, and every family has at least one relative who makes you question the Geneva Conventions.

So with Thanksgiving and Christmas knocking, Abdul Hakim-Shabazz talked with Alexandra Hudson, author of The Soul of Civility, to get some wisdom for those of us preparing to sit across from Crazy Aunt Agnes, Uncle Blah Blah, or That Cousin Who Thinks Facebook Is a Peer-Reviewed Journal.

The Enneagram + Marriage Podcast with Christa Hardin: Culture Wars, The Family Table, and True Civility with Author and Storyteller Alexandra Hudson

Mentor in Residence Opportunity

We are seeking an extraordinary person to join our family and the Civic Renaissance team as a Mentor in Residence. This role is for someone who loves children, loves learning, and wants to help cultivate a rich atmosphere of curiosity, beauty, kindness, and intellectual life for three young children ages five, three, and one.

Our home is an atelier, a space of creativity, innovation, learning. It is a place of ideas, stories, nature, music, art, conversation, and unhurried discovery. We are building an educational model for our family that brings together nature exploration, early literacy and numeracy, storytelling, cultural formation, ample leisure and unstructured free time, and the joy of hands-on making. We hope to share this model with other families over time.

We are looking for a guide who brings presence, steadiness, imagination, and an instinct for wonder. You do not need classroom experience. We care about your character, your curiosity, your capacity to listen well, your intellectual interests, and the way you see children and human flourishing.

This is a national search, and we welcome candidates who are open to relocating to Indianapolis. Please share widely.

Year Ago on Civic Renaissance:

My mother, The Manners Lady, taught me that the rules of etiquette were sometimes meant to be broken

Thank you for being part of our Civic Renaissance community!