Efficiency Is Making Us Less Human

Kahlil Gibran and Jacques Ellul on what modern systems can’t measure, and what we lose because of it

Gracious reader,

Kahlil Gibran and Jacques Ellul were both born this week, on January 6.

Kahlil Gibran was born in 1883 in Bsharri, Lebanon, under Ottoman rule, the same year Karl Marx died, five years before the Berlin Conference formalized European imperial control over much of the world, and at the start of a period of mass emigration that would soon reshape American cities like Boston.

Jacques Ellul was born in 1912 in Bordeaux, France, one year after Frederick Taylor published The Principles of Scientific Management and two years before World War I, as industrial efficiency, centralized bureaucracy, and technological optimism reached their peak.

They could hardly be more different in style or reputation. Gibran became one of the most widely read poets of the modern era, author of The Prophet, a book that has lived quietly in people’s homes, marking weddings, funerals, grief, love, and private reckoning for a century. Ellul, by contrast, was a legal scholar, theologian, and public servant, best known for The Technological Society, one of the earliest and most serious critiques of modern technological life.

Long before smartphones, social media, artificial intelligence, and far prior to it being fashionable to be a tech-skeptic, Ellul warned that efficiency would become a ruling value, reshaping institutions and, eventually, human beings themselves. Gibran protected the interior life from reduction; Ellul exposed the systems that try to reduce it anyway. Together, they remain essential guides for a world that keeps mistaking what can be measured for what actually matters.

Both thought deeply about what it means to be human, which is why they belong in the Great Conversation, the long, iterative dialogue about life’s biggest questions, and why their work sits at the heart of Civic Renaissance.

Gibran: forming a human vision from exile and attention

Gibran’s sensibility was shaped early by displacement and precarity. Born in Ottoman-era Lebanon, he immigrated to Boston as a child with his family, poor and largely invisible by the standards that sort people quickly. They lived among other immigrants in settlement housing. At Denison House, a settlement house for refugees, Gibran’s talent for drawing was noticed by a discerning adult who paid attention rather than tallying deficits. That moment mattered. His life could have been assessed, categorized, and dismissed. Instead, he was seen.

That experience never left him.

Gibran grew up carrying real responsibility. His father’s imprisonment and later death left the family financially vulnerable, and Gibran’s art and writing were not hobbies. They were how he helped keep his family afloat. Work, for him, was never abstract. It was bound up with duty, care, and provision. That history clarifies why he writes about work not as productivity but as moral offering.

The Prophet (1923) is composed of twenty-six prose poems addressing the ordinary elements of a human life: love, marriage, children, work, giving, sorrow, joy, death. Gibran began working on the book in 1912 and held it back for years. He explained why:

I kept this manuscript for four years before I delivered it over to my publisher because I wanted to be sure, I wanted to be very sure, that every word of it was the very best I had to offer.

He chose poetry because poetry resists reduction. It cannot be optimized or extracted for metrics without being destroyed. The book opens with a figure Gibran calls “the chosen and the beloved,” preparing to leave the town of Orphalese. Before he departs, the people ask him to speak about how to live.

On joy and sorrow, Gibran writes:

Your joy is your sorrow unmasked.

And the selfsame well from which your laughter rises was oftentimes filled with your tears…

When you are joyous, look deep into your heart and you shall find it is only that which has given you sorrow that has given you joy.

Gibran’s insight here is reminiscent of a story Socrates tells about the relationship between pleasure and pain in the Platonic dialogue the Phaedo—also a manifesto about the importance of the immaterial amid a world that values the corporeal. In reflecting on his recent, unjust conviction and death sentence, Socrates speculates about the nature of pleasure and pain. “It would make for a good fable from Aesop!” Socrates quips before telling the story: “God wanted to stop their continual quarreling, and when he found that it was impossible, he fastened their heads together; so whenever one of them appears, the other is sure to follow.”

Socrates says that pleasure and pain are apparent opposites, but are also two sides of the same coin. This is why we often experience them together—as someone who loves spicy food, I can attest to this! But Socrates is also getting at a deeper insight into the human experience: Often, after we have endured great suffering, the good things in life—perhaps the simple pleasures we took for granted before—are that much more delightful.

Gibran on giving:

You give but little when you give of your possessions. It is when you give of yourself that you truly give.

On eating and drinking:

Would that you could live on the fragrance of the earth, and like an air plant be sustained by light. But since you must kill to eat, and rob the newly born of its mother’s milk to quench your thirst, let it then be an act of worship.

And on work:

All work is empty save when there is love; and when you work with love you bind yourself to yourself, and to one another, and to God…

Work is love made visible. And if you cannot work with love but only with distaste, it is better that you should leave your work and sit at the gate of the temple and take alms of those who work with joy. For if the bread you bake with indifference, you bake a bitter bread that feeds but half a man’s hunger.

Gibran’s insistence is clear. Meaning lives in attention, love, and responsibility, not in output. Once we begin measuring the soul, we stop listening to it.

Ellul on the perils of optimization

Ellul arrived at the same conclusion from the opposite direction.

Unlike Gibran, he did not come to the question of dehumanization through exile or marginality, but through immersion. He grew up in Bordeaux in a modest household, the son of a Serbian immigrant who worked as a commercial agent and struggled to maintain financial stability. There was no inherited political authority, no elite cushion. What Ellul absorbed early was precarity, discipline, and the quiet pressure of making institutions work for people who depended on them.

He was trained as a lawyer and entered the world of law, bureaucracy, and public administration on its own terms. He understood how rules are made, how procedures harden, how systems begin with good intentions and end by prioritizing their own survival. He learned, from the inside, how easily institutions slide from serving human beings to managing them.

That education was sharpened by history.

When France fell and the Vichy regime aligned itself with Nazi Germany, Ellul was dismissed from his university post. Law, which had promised order and protection, now collaborated with the dehumanizing Nazi regime. Categories, files, permits, lists. He watched the machinery of administration turn people into cases and schedules. Jewish families became entries to be processed. Efficiency did not look neutral anymore. It looked lethal.

During the Second World War, Ellul joined the French Resistance. He helped warn Jewish families of impending arrest and assisted them in finding refuge. These people were being reduced to lists, schedules, and administrative categories. Ellul responded with prudence, and risk, not because a system told him to, but because he recognized their humanity.

After the war, Ellul entered public life, serving as Deputy Mayor of Bordeaux. He wanted to help rebuild a fractured society. He wanted to see whether institutions could be turned back toward human ends. The experience disillusioned him. He watched procedure replace responsibility. He watched success measured in outputs while deeper damage went unaddressed. After two years, he left politics, convinced that systems could run smoothly while hollowing out the people inside them.

Ellul did not reject institutions from the outside. He tested them from within. He learned their language. He saw how easily efficiency becomes a moral substitute, how quickly rules relieve people of the burden of seeing one another as human beings.

This is what gives weight to The Technological Society. Ellul is not railing against machines and technology. He is naming a habit of mind, and describing what their precursors did to us, and what their current manifestations do to us now: they foster a way of thinking that treats human life as a technical problem to be solved rather than a moral reality to be honored. It promoted a way of organizing the world that prizes speed, scale, and predictability, even when those virtues come at the expense of attention, responsibility, and care.

Where Gibran learned the cost of reduction through exile and invisibility, Ellul learned it through proximity to power and process. One guarded the interior life. The other exposed the systems that quietly train us to forget it.

Both arrived at the same warning from opposite ends of the human experience. When efficiency becomes the highest good, people begin to resemble machines. And once that happens, no amount of technical brilliance can restore what has been lost.

Ellul spent the rest of his life naming what he had seen. His most famous work, The Technological Society, first published in French in 1954 under the name Technique: The Wager of the Century. It was translated into English ten years later in 1964 and popularized in America by Aldous Huxley, the author of Brave New World.

It is not about gadgets or screens. It is about a way of thinking that quietly takes over a civilization. He called it technique.

Ellul defined “technique”, the single greatest threat to modern society, this way:

In our technological society, technique is the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity.

In over-valuing protocol and efficiency in every realm of human life, Ellul says, we overlook and undermine many important aspects of the human experience.

Once efficiency becomes the supreme logic, means replace ends. We don’t see human beings in the fullness of who they are: beings with dignity and equal moral worth.

We see them instead by virtue of utility, their usefulness to us, to society.

Instead of asking whether something is good, just, or fitting for human life, institutions ask whether it works. Faster. Cheaper. More scalable. Questions of meaning give way to questions of performance.

Wisdom gives way to procedure. Decisions are no longer made by people exercising discernment, but by systems following rules. Responsibility dissolves into process. No one is accountable, because everyone is following protocol.

Human beings adapt to systems instead of the other way around. Time is reorganized. Attention is fragmented. Life is paced by clocks, metrics, and schedules rather than by hunger, rest, relationship, or need.

Freedom narrows without anyone choosing it. The efficient option becomes the only imaginable one. Moral language erodes. Words like wise, just, good, right, gracious, and humane start to feel imprecise or naïve.

Ellul describes the result with chilling clarity:

Technique has penetrated the deepest recesses of the human being. The machine tends not only to create a new human environment, but also to modify man’s very essence… He was made to eat when he was hungry and to sleep when he was sleepy; instead, he obeys a clock… He was created with a certain essential unity, and he is fragmented by all the forces of the modern world.

And later:

Technique has taken over the whole of civilization. Death, procreation, birth all submit to technical efficiency and systemization.

Ellul is not offering a program or a solution. He is diagnosing. He wants readers to see the logic shaping their lives so that discretion, responsibility, and humanity are not quietly surrendered to systems that claim to know better.

But Ellul’s concern is about far more than technology. Ellul is concerned that in our fixation with specialization and technique, especially in our modern universities, we’ve lost a holistic vision of the human person—and have thereby imperiled the education required to cultivate truly whole persons.

And on this score Ellul is again in good company.

Socrates said that techne (Greek for knowing and making) could be good only when deployed with sophia (Greek for wisdom). Many years later, C.S. Lewis, a contemporary of Ellul, echoed this idea in his famous essay, The Abolition of Man: technique that is not guided by wisdom has the potential for disastrous consequences, including the very abolition of mankind itself.

For Ellul, technique and the modern “cult of efficiency” come at the expense of thinking holistically and globally. Have you ever been encouraged to “Think globally, act locally?” Ellul actually coined that phrase: He wrote in his Perspectives on Our Age, “By thinking globally I can analyze all phenomena, but when it comes to acting, it can only be local and on a grassroots level if it is to be honest, realistic, and authentic.”

He was worried, however, that our current era’s ethos— defined by focus on “practical” vocations and areas of study, such as the STEM disciplines, business, or marketing—inhibits us from either thinking globally or acting locally, and from cultivating our humanity, too.

Choosing the human in a world of optimization

What matters in human life is not efficiency, output, or optimization.

What matters is prudence, or practical wisdom: the ability to discern what is fitting in a particular moment with particular people.

What matters is attention, the capacity to see another person as they are, not as a category or obstacle.

What matters is responsibility, owning the consequences of our choices rather than hiding behind process or protocol.

What matters is relationship, the slow accumulation of trust, loyalty, memory, and shared life.

What matters is meaning, the sense that our actions participate in something larger than immediate results.

None of these can be measured without being distorted.

When what can be measured replaces what matters, decisions stop being about what is right and become about what is defensible. People stop being encountered and start being managed. Disagreement stops being a condition of shared life and becomes a threat to be eliminated. Responsibility is displaced onto systems, metrics, and experts. Human beings begin to feel interchangeable, unseen, and disposable, even when no one intends harm.

This is not a moral collapse driven by bad actors. It is a category mistake. We begin treating human life as if it were a technical problem, and technical solutions cannot answer human questions.

That is the danger Ellul is naming.

That is what Gibran is protecting against.

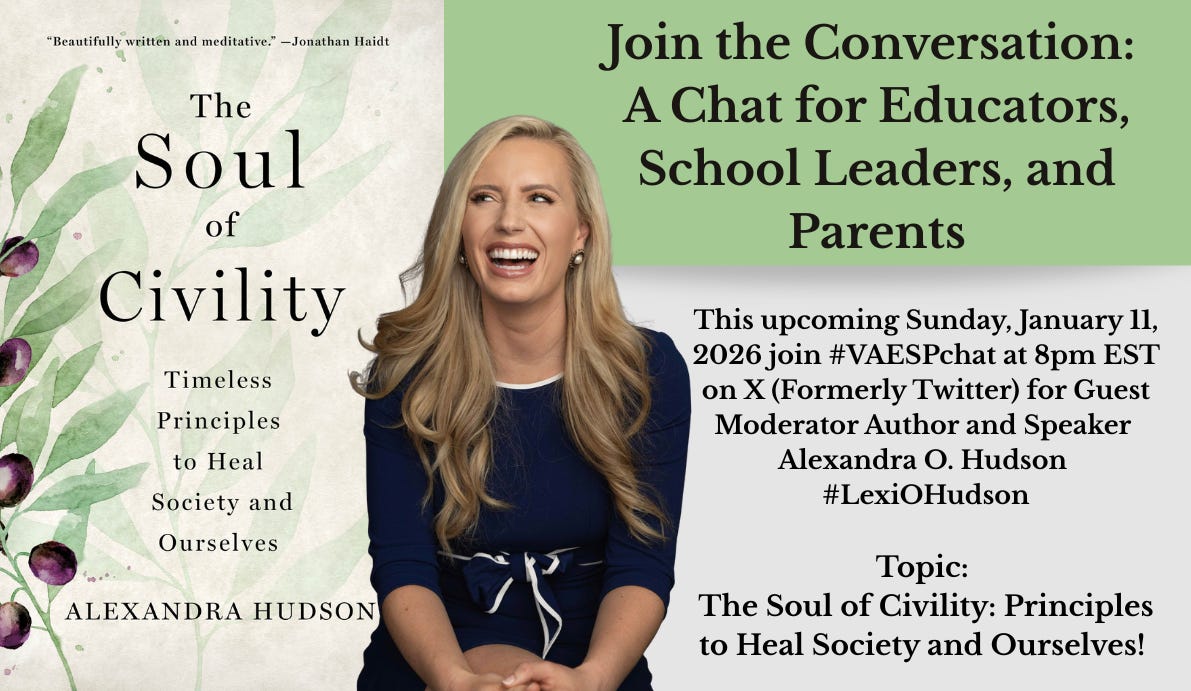

The Civic Renaissance tour: what it means to be human in the age of the machine

This is central to Civic Renaissance: the goal of this work is not to win arguments or design better systems. It is about restoring the conditions under which people can thrive without dehumanizing one another. It begins and ends with helping us re-discover the gift of being human, in ourselves and in others.

Across The Soul of Civility, Civic Renaissance, and now the tour, the claim remains the same: civic renewal is first a human task, not a technical one.

This work does not abolish efficiency and systems; it stays mindful of humanity amid them.

This work does not promise to fix conflicts or resolve controversy. It equips people to exercise judgment, restraint, and recognition in the middle of disagreement, day in and day out.

Gibran insists that the interior life cannot be neglected without cost.

Ellul insists that systems will neglect it by default.

This work lives in the space between them, defending what cannot be measured in a world that keeps trying to measure it anyway.

Some questions for you to consider:

Where in your own life do numbers, metrics, or efficiency crowd out things you know matter more, such as attention, care, or responsibility?

What is something in your life that would be diminished or distorted if you tried to measure it?

Can you think of a time when something “worked” on paper but felt wrong in practice? What did you notice, and what did you do?

Where do you see the cult of efficiency corroding our humanity most egregiously today?

What is one small, ordinary place in your life where you could resist reduction and show up more fully human?

Do you think it’s possible to stay humane toward one another without resolving the underlying conflict? What would that look like in practice?

I’d love to hear what you think. Please share your thoughts in the comments.

Thank you for being part of the Civic Renaissance community!

In case you missed it: Alexandra Hudson and Mitch Daniels at the Civility Summit

In the news

“Author launches national civic renaissance tour in Shelbyville,” The Shelbyville News

The Shelbyville effort is being led locally by Pastor Ralph Botte of First Christian Church of Shelbyville, who invited Hudson to help launch a community-wide initiative inspired by her book.

“When I read The Soul of Civility, it gave language to a problem I was seeing every day in Shelbyville,” Botte said. “People wanted to engage across differences without tearing relationships apart, but we didn’t have a shared framework for doing that. The book clarified what was missing: a way to practice civility that goes beyond surface politeness and is grounded in human dignity. That’s what led me to reach out to Alexandra. As we began sharing the book locally, people recognized themselves in it and wanted to take responsibility for living these ideas together.”

The Civic Renaissance Tour represents the next phase of Hudson’s work, building directly on the impact of The Soul of Civility. Since its release in 2023, the book has been taken up by community leaders, universities, and bipartisan legislative groups across the United States and abroad as a practical framework for engaging disagreement without dehumanization and for reclaiming responsibility at the local level. Rather than remaining a theoretical work, the book has repeatedly served as a catalyst for concrete civic initiatives. In an age marked by polarization and distrust, The Soul of Civility asks a central question: how can people flourish across difference?

Following the book’s publication, Hudson, often traveling with her husband and three small children, visited 136 cities across five countries. She spoke in venues ranging from local libraries and churches to Stanford University, Yale Law School, the Canadian Parliament, and the UK House of Lords. In city after city, the book sparked not only conversation, but sustained local action.

“The Civic Renaissance Tour grew out of listening,” Hudson said. “Everywhere I went, leaders were asking how to live these ideas together, not just talk about them. I realized my role was not to visit and lead every community, but to help local leaders build the capacity, relationships, and support they need to carry this work forward every day.”

The Shelbyville launch follows Hudson’s demonstrated framework for community renewal, a four-phase process that moves communities from shared understanding to sustained local practice. The effort begins with residents reading The Soul of Civility together, followed by Hudson’s visit for a public event and leaders’ roundtable. From there, local leaders across sectors will take responsibility for carrying the work forward in daily civic life, with the long-term goal of Shelbyville serving as a regional hub for civic renewal.

The Shelbyville engagement will begin with a community-wide public event on Thursday, January 29, at 7:00 p.m. at First Christian Church of Shelbyville. The following morning, Friday, January 30 at 9:00 a.m., Hudson and Botte will convene a leaders’ roundtable. During the roundtable, a select group of Shelbyville leaders will work together with Hudson to develop a practical action plan for implementing the book’s ideas and fostering long-term civic renewal in the community.

Hudson’s work with Shelbyville follows a demonstrated and repeatable pattern.

In Carmel, Indiana, City Councilor Jeff Worrell contacted Hudson after reading The Soul of Civility to explore how its ideas could be embedded locally. That effort culminated in the Carmel Civility Summit, which convened more than 100 mayors, city council members, commissioners, and civic leaders from 17 states and Canada. “The Soul of Civility was a roadmap that led me to invite Alexandra to speak and launch a civility effort in Carmel,” Worrell said. Former Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels and Hudson opened the summit with a fireside conversation on civility and leadership. “You’ve only begun to hear from this amazing young woman,” Daniels said.

In Zionsville, former Deputy Mayor Kate Swanson partnered with the Mayor’s Youth Advisory Council to integrate The Soul of Civility into the council’s core curriculum, grounding civic formation in a shared moral framework. The council then convened a public community discussion with Alexandra Hudson at the Hussey-Mayfield Memorial Public Library, drawing a standing-room-only audience and signaling broad public engagement across generations.

“Every person, and especially every young person, in America needs to read The Soul of Civility,” Swanson said.

In Muncie, The Soul of Civility was chosen as a citywide community read, anchoring a shared civic conversation across residents, institutions, and local leaders. State Rep. Elizabeth Rowray partnered with the Muncie Chamber of Commerce to invite Alexandra Hudson to keynote their Christmas banquet, where every attendee received a copy of the book as a call to carry the work into their own civic and professional lives.

Communities across Indiana, including Fishers, Valparaiso, South Bend, Evansville, New Albany, and Salem, are now implementing similar initiatives inspired by Hudson’s work.

Nationally, The Soul of Civility is informing freshman orientation programs at Ivy League universities and is being read in bipartisan book clubs within polarized state legislatures. The book has earned praise from leaders and public intellectuals across the political spectrum, including Francis Fukuyama and Jonathan Haidt.

The Civic Renaissance Tour formalizes this growing momentum by offering communities a structured pathway to move from shared ideas to sustained local practice. Additional tour stops include Colorado Springs, Colorado; Urbandale, Iowa; Sacramento, California; Austin, Texas; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Toronto, Canada; and London, England, with more locations to be announced.

“My vision is to help unlock an era of human flourishing in our country,” Hudson, who lives in Indianapolis, said. “That work begins when people stop waiting for rescue and start taking responsibility for the communities they are shaping together. We each have way more power than we realize to be part of the solution.”

She continued, “Ralph, First Christian Church of Shelbyville, and the greater Shelbyville community are showing what that looks like in practice. I am honored to partner with the leaders of Shelbyville in this work.”

As the kickoff city of the Civic Renaissance initiative, Shelbyville is helping shape and refine a new model of community renewal rooted in Alexandra Hudson’s The Soul of Civility. The city is piloting the framework as it moves from idea to practice, generating lessons that other communities can adapt to their own contexts. By launching the Civic Renaissance Tour in Shelbyville, local leaders are contributing to an emerging national effort to strengthen civic life by investing in their own capacity to lead and flourish.

To join the Civic Renaissance movement, or to bring the Civic Renaissance Tour to your community, apply to be a Civic Renaissance Ambassador!

Join us for a chat for educators, school leaders, and parents

Year Ago on Civic Renaissance:

Can conflict strengthen relationships?

Thank you for being part of our Civic Renaissance community!

Thank you for this Lexi - I wasn't aware of Jacques Ellul's work. I think Neil Postman developed this idea later on with the Technological Society. Gibran of course is always an inspiration.

I think some of our fear of AI is rooted in this 'robotization'. We are afraid of being replaced by better robots because we have lost the sense of our own humanity.

Our World Philosophy Day talk this year was exactly about that - I wrote an approximate transcript in my own Substack:

https://artistoflife.substack.com/p/being-human-in-an-artificial-age

Cheers

Gilad

Efficiency should have a soul